The Great Race Between Water Conservation and Climate Change

Image: “Watering the sky, Carbondale, Colorado”

To stay ahead of climate change we’ll need to double down on water conservation in cities and on farms.

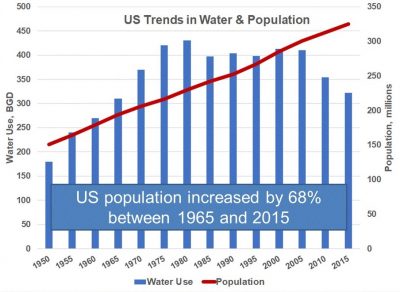

Over the past 50 years the population of the United States grew by two-thirds and its economy tripled. Yet we are using no more water today than we did a half-century ago, according to recently released US Geological Survey stats.

That’s a pretty remarkable accomplishment, and it has undoubtedly moderated the risks and impacts of water shortages in places like California, Texas, and in the Colorado River basin in recent decades.

For much of human history, increased water diversion has served as an essential booster for our economic growth rocket, but around 1980 the water booster decoupled from the growth curves and fell away while our population and GDP continued to soar. During the past four decades our overall water use declined by 25%.

Our per-capita water use can be expected to continue dropping in coming decades, according to an impressive new study published in the March issue of Earth’s Future. Tom Brown, an economist in the US Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station and his two co-authors project that per-capita water use could drop by another 25% between now and 2060……assuming a stable climate. However, when they factored in projections from climate change models, they found that rising temperatures will drive substantially greater needs for more water in crop and landscape irrigation, and in meeting heightened electricity demands in coming decades. As a result, Brown and his colleagues project that per-capita water use will drop by only 16% (instead of 25%) and our total water use will increase by 22% as our population grows by 44% by 2060, creating enormous additional risk of water shortages in many parts of the country.

The authors found that adding more reservoir storage won’t do much to alleviate severe water shortages simply because there won’t be water to fill the reservoirs. This reality led them to conclude that “Reductions in agricultural irrigation will be essential to contain shortages in other water use sectors and avoid excess groundwater drawdown or environmental flow losses.”

Fortunately, the researchers found that only modest (<5%) reductions in consumptive water use for farm irrigation would go a long way to alleviate water shortages in many at-risk water basins in the Western US; however, in some Southwestern basins, more than 30% reductions in consumptive use will be needed.

While these water-saving imperatives sound daunting, my own research suggests that savings of 30-50% in irrigated agriculture are in fact feasible. My research team has documented that consumptive water use can be reduced substantially by changing irrigation equipment or watering practices, shifting to less water-intensive crops, improving soil health to better retain moisture, or temporarily fallowing farm fields. These water savings are possible even while maintaining current levels of agricultural productivity.

I’m also betting that many US cities are going to continue pushing down their water use to levels substantially lower than Tom Brown’s team assumed in their hydrologic forecasts. In fact, it’s already happening: in just the past 15 years, Denver has cut its total water use by 28%, Los Angeles by 23%, San Diego by 22%, and Austin by 17%, to highlight just a few. And these cities have accomplished these water-use reductions while their populations have grown by 28-38%.

Climate change will undeniably present us with ever-greater challenges in balancing our water budgets and averting shortages. But the silver lining is that we CAN prevent water scarcity from worsening in the near term, and with aggressive conservation we can begin reducing water scarcity over coming decades even while climate change intensifies. Modeling studies like Brown et al. can help us to understand the complex interactions between shifting water availability and use, but the outputs of those models depend greatly on our assumptions about what can be done with water conservation and improved efficiencies going forward.

We need to keep pushing ourselves to use less and less water. In forthcoming posts I’ll share more evidence of cities and farmers that are leading the way toward a more water-secure future. Stay tuned.

Brian